In recent years hundreds of Chinese lawyers and activists have been arbitrarily jailed under a new form of detention. All of them were held in solitary confinement, and many were subjected to torture. In a new book, twelve individuals tell their personal experiences from inside the secret prisons of China.

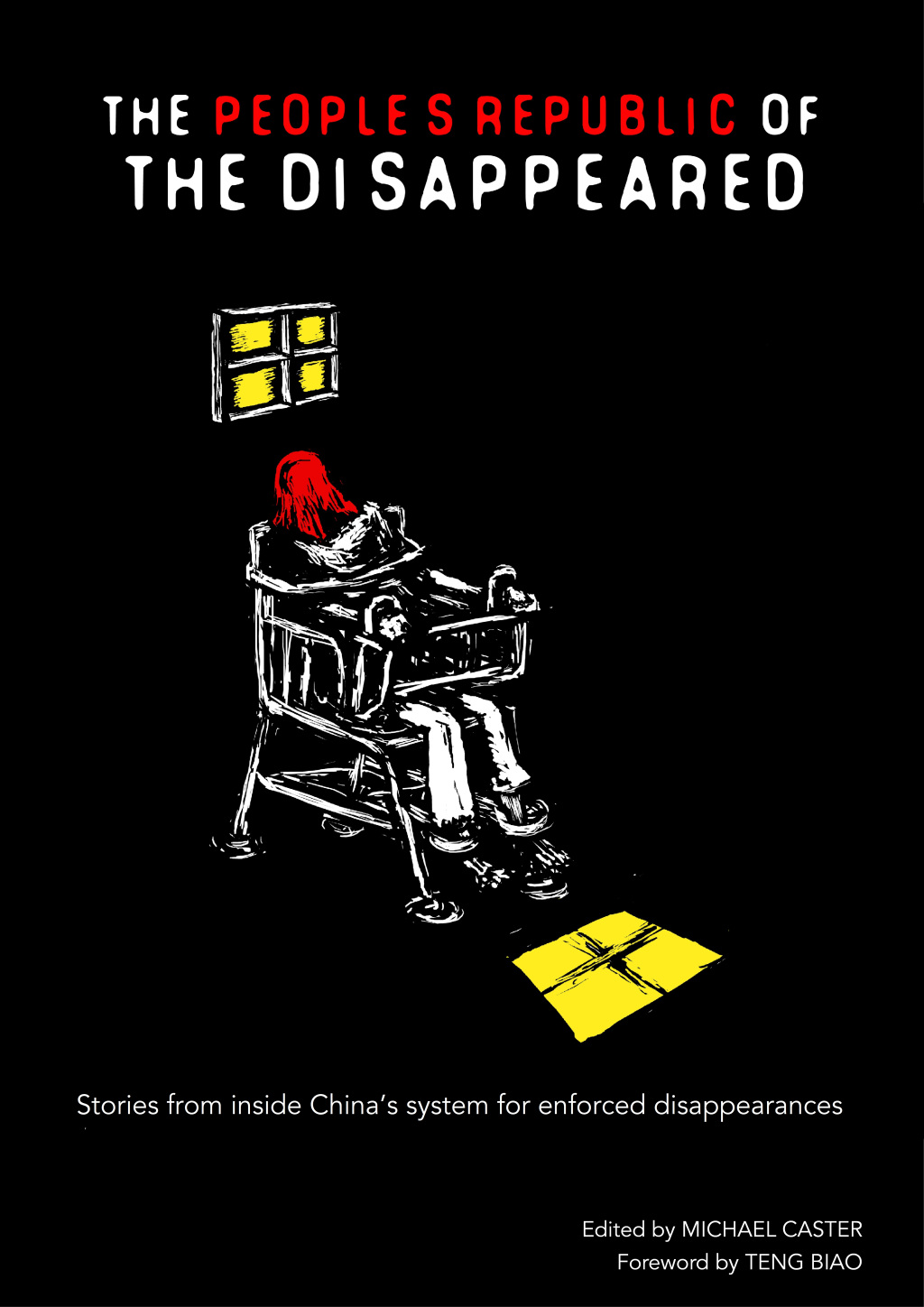

Shackled, starved, beaten up and forced to sing the national anthem after being stripped naked. Those are just a few of the first-hand experiences told in the new book The People’s Republic of the Disappeared: Stories from inside China’s system for enforced disappearances.

The book contains 12 personal accounts from individuals who were held at secret locations in China under “residential surveillance on a designated location” (RSDL), a new form of detention introduced into Chinese criminal law in 2013. As reported earlier this year in Taiwan Sentinel, RSDL in practice means that any person can be held and isolated at a secret location for up to six months without any legal process whatsoever.

This detention form not only violates international law; it is also an invitation to torture. As even the prosecutor might not be allowed to visit a detainee, any evidence of torture is almost impossible to come by. Ask Wang Yu, the high-profile lawyer who was the first to be detained when the “709 crackdown” began in the summer of 2015, eventually resulting in the disappearance of 300 lawyers and activists across China.

Over a year after her enforced disappearance, a video clip showed Wang “confessing” to collaboration with “foreign forces” to undermine the Chinese government. For the first time, in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared she speaks at length about her kidnapping as well as her treatment during detention, which included being forced to wear shackles for days on end, and being deprived of sleep and water until she fell unconscious.

Over a year after her enforced disappearance, a video clip showed Wang “confessing” to collaboration with “foreign forces” to undermine the Chinese government. For the first time, in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared she speaks at length about her kidnapping as well as her treatment during detention, which included being forced to wear shackles for days on end, and being deprived of sleep and water until she fell unconscious.

The risks of RSDL are by no means limited to Chinese citizens. Since Taiwanese activist Lee Ming-che is not yet free he is only mentioned as a footnote in the book, but the collection of first-hand accounts provides hints as to the conditions Lee may have had to endure since his enforced disappearance at Macau International Airport in March this year.

Peter Dahlin, a Swedish activist who was kidnapped at his Beijing home in January 2016 and expelled from China after 23 days in a secret prison, is the only foreigner among the 12 individuals whose stories are told in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared. His experiences have been described in earlier interviews, and at length in the Guardian.

However, for the first time ever, his girlfriend, Pan Jinling, also steps forward to talk extensively about her experiences when she was held in solitary confinement on another floor in the same building as Dahlin. The story serves as yet another example of how friends and family are also regularly punished when their loved ones are suspected of crimes against Chinese national security.

With the permission of Michael Caster, editor of The People’s Republic of the Disappeared, Taiwan Sentinel is reproducing excerpts from one of the personal stories told in the book. The experiences are those of Chen Zhixiu, a pseudonym, who was born in 1979 in Sichuan Province. Besides working as a human rights lawyer, Chen also researched and taught ways to use the Chinese law in politically sensitive judicial cases.

In early 2016, Chen was placed in RSDL for a month before being released on bail and prohibited to leave his native Chengdu without police permission. While he was not tortured with electrical shocks or forced medication, his case highlights the mental torture and deprivation of food and sleep that are systematically used to break detained individuals.

Needless to say, even after his “release,” surveillance and pressure and travel restrictions have prevented Chen from continuing his job in an efficient manner.

Excerpt: Chen Zhixiu’s story

It was early February, around 10am. I was preparing to leave to meet a friend for lunch when suddenly a group of people burst into my apartment. Somehow, it seems they had keys for the gate outside and for my front door. There were only three or four inside, but I could see many more lurking in the corridor and on the stairs, maybe a dozen in total. They must have been monitoring my computer and phone, as they seemed prepared for anything. Was there a bug in my room?

I would soon find out that they already knew my password and had accessed my normal email account but hadn’t accessed or didn’t know about my encrypted email. Maybe they had installed surveillance equipment in my house, and could see my computer screen. This seemed to prove that the government could monitor anyone, even those living in temporary rental accommodation.

I knew that the police had harassed my neighbors before I had left for a work trip out of China, and that they had also disturbed them while I was away. I later found out that while I was away the police had tricked my neighbors into going to the police station and had made copies of the house keys. This must be how they installed surveillance equipment when I was away but I had no idea their technology was so good. They must have seen all my emails and discussions about friends who had already disappeared into Residential Surveillance at a Designated Location (RSDL). It seemed hopeless, trying to second guess what they might know.

I was worried what they might do to me in order to force their way into my computer for the rest of the information they wanted. But at least I had already securely deleted a lot of sensitive case information from my hard drive so that they would be limited in what they could access after they took me. Still, I was trying frantically to remember what I had and hadn’t managed to delete so I would be better prepared for the range of interrogations, and so I could do my best to protect others involved.

I had known they would eventually come for me. I couldn’t escape this misfortune. They had “invited me for tea” [A euphemism for a police summons] several times in the past few months. They asked about friends who were being held in secret detention. They had even kept me overnight in a police station a few weeks before. On that day, I had been planning to meet another lawyer, but before I could a Public Security Officer from Chengdu had unexpectedly called asking me to meet him. When I arrived, he was with Beijing Public Security officers. They kept me in the police station overnight. After they released me, I found out that another lawyer I knew had disappeared while I was in the police station. Things were getting serious.

After that night, Chengdu Public Security had come for me several times, accompanied by their Beijing counterparts. They had mainly asked about my relationship with a few key individuals in the rights defense community. I would tell them that I was just a lawyer hired by a small group of rights defenders to facilitate trainings for “barefoot” lawyers. The police had raided several of these training sessions so there was no point in me hiding my involvement with them.

After someone close to me disappeared, I had started to prepare for my own inevitable disappearance. I had arranged for my own lawyer in case I was taken, and set up an emergency contact. I left copies of my power of attorney at the offices of two lawyer friends and wrote letters to my parents and ex-girlfriend. I contacted a diplomat I knew and the Chinese Human Rights Lawyers Concern Group in Hong Kong, making sure they knew the lawyer I wanted to represent me if I was taken. At the same time, I had been destroying sensitive case documents, writing down questions to share with partners who had not yet been taken, and making a plan for how we would react to police interrogations. After that, I was just waiting for them to come.

Somehow, I felt relaxed when they arrived, standing there in my small rented apartment. I was surrounded by threatening security agents and yet I was kind of happy. I had been so nervous over the previous days, unable to really concentrate on anything other than remembering to always look over my shoulder. I remember a friend had tried to convince me to escape from China, but I had no idea where to go, and so I had just been waiting. At least, when they burst into my apartment, I didn’t have to be nervous about it anymore.

[…]

It took a long time to arrive at our destination, a length that was only compounded by the total darkness of having a hood covering my head. I couldn’t see anything. All I knew was that we arrived in a parking lot and then I was taken up in an elevator, made to walk down a corridor into some room, and then confined in an interrogation chair.

I was made to wait for a long time. Nobody took off my hood but at one point I overheard someone on their walkie-talkie saying how someone else I knew had arrived. Would no one be spared? At least I had already done everything I could to prepare. I just hoped everyone else would react to the interrogation as we had discussed.

They had locked the board at the front of the interrogation chair, which pushed against my legs. I lost sense of time but I knew it was a long while. My head was still hooded but I focused on a tiny sliver of light from the direction of my chin.

When they finally came to remove the hood, it was suddenly dazzling, so many lights pointed towards me. I could see the place was well constructed. The walls were specially designed, padded for sound insulation and suicide prevention. There was an interrogation table, a big-screen television, speakers, a computer, and cameras in the room. There was a digital clock, displaying the date and time. I could see it was about 9pm. It had been almost 12 hours since they had stormed my apartment.

They gave me a medical examination. I told them that my heart and cervical vertebra were not so good. They tested my blood pressure. They were about to do an EKG but skipped it because there wasn’t a power supply.

They searched me. They took away everything I had with me. They even took away my belt, shoes and socks. I accepted that I was going to be interrogated barefoot. I had heard that these days were the coldest in 30 years. I could feel the chilliness of the floor. This was just the beginning; I would feel the same over the coming days.

I was being held on the first floor. That’s why it was really cold.

The second morning after I was taken, the guard took off all my clothes, made me stand naked on the cold floor, and sing the national anthem [In September 2017 China passed a law making it a crime to disrespect the national anthem]. I asked them if the national anthem could only be sung while showing one’s genitals. He didn’t respond. I thought about the meaning of the line that says stand up, ye who don’t want to be slaves, and so I sang loudly, defiantly, singing and staring directly at them with anger.

“Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!” I shouted. They stopped me and told me to get dressed.

I wasn’t allowed to rest at all for the first three days. Even during the short breaks between interrogations, there were always two people watching me.

When they finally let me have some rest, I wasn’t really allowed to sleep. They didn’t allow me to wear any clothes to bed. The room was so cold, even though they had given me a blanket. I still couldn’t handle that kind of cold. I was naked. A guard would come into my room and lift up the blanket to check if I was asleep. He pushed me around or hit my face, making excuses that it was to make sure I was still alive, and it was for my own good. I really wanted to swear at them. So even after they agreed to let me rest, I couldn’t really sleep. This situation continued for more than 10 days.

[…]

During the first three or four harsher days, my three interrogators acted out different roles. The main interrogator, I think his name was Yao, was often gentler than the others but he would still occasionally strike the table as a warning if he didn’t like my answers. The second one, let’s call him Liao, was very tough, unfriendly and deceitful; he often yelled at me not to be shameless, saying he was giving me a chance to save face. Another one, a young fellow, I called Little Zhang, was impatient. It seemed he wanted me to cooperate with him mostly just so he could spend less time having to deal with me. They all took turns.

Yao would tell me that I shouldn’t collaborate with foreigners because they were able leave at any time but I was Chinese and couldn’t escape even if I wanted to. Liao would make things difficult for me when he was interrogating me alone. The young one, Little Zhang, struck me as kind of casual. He often told me to let him know if I needed any daily necessities, pretending to be my friend, as if I could believe any of my captors had my best interests at heart or that I would be tricked into divulging some secret because one interrogator smiled at me more than the others.

After a while, they changed the focus of their interrogation outside my immediate circle. They asked me about many human rights incidents that have taken place recent years. They were specifically curious about the China Human Rights Lawyers Group.

They thought I wasn’t really directly involved with many cases and I think they believed me when I denied supporting human rights work from behind the scenes. Before I was taken, but when I knew I was going to be detained, I had thought they would interrogate me about Wang Quanzhang, but in fact they didn’t really ask me about him at all. He had only recently been formally charged after being held in secret for over six months and I knew several people who had been closely working with him but I convinced my interrogators that I had never worked directly with him, which in a way was true. They only asked me about Wang Quanzhang twice.

Throughout my interrogations, they used threats and psychological tactics. They would casually ask me if I thought my parents were healthy enough to survive my situation. They dug so deeply, the interrogators, to picture future outcomes and how that would impact my family. For example, if I was sentenced to 10 years, would my mother’s health last that long? They mentioned examples of human rights workers whose families had died waiting for their loved ones to serve out their prison sentences. This approach really gave me a lot of anxiety.

I knew it was all threats and lies but the tactic worked. I did consider my parent’s health. My mother’s condition was already bad and I was honestly worried about whether she would be able to handle this. When the interrogators left me alone, my mind would wander to my parents. I wondered if they were already sick from learning about my disappearance or if they had gone to the hospital. I knew I couldn’t do anything, but I couldn’t stop myself from thinking about it. I have to admit, such psychological tactics worked well on me.

My interrogation sessions were filled with all manner of deception. They tried telling me that all my friends had already confessed, that they had put all the responsibility onto me. I didn’t believe them, but by then I had been in their custody for several weeks and it was getting harder to resist. To convince me that my friends had sold me out, they showed me one confession letter they claimed was from one of my partners. They claimed that all my friends had already recorded video confessions and told me that I needed to do the same, that the video was for their superiors and if they were satisfied then I could be released. I agreed to be recorded, anything to put an end to my sleep deprivation and humiliation.

Since I had arrived, I hadn’t been allowed to shower. I felt that my face and hair were full of oil. My nails were black. The first shower I had was because they wanted me to look clean for the video. I was allowed to brush my teeth and take a shower but I didn’t have any clothes to change into. My clothes were never washed while I was inside. I could feel that my body had a peculiar smell but I kind of got used to it after a while.

[…]

In the last five days before they let me go, they started to interrogate me again, frequently. They prepared some papers for me to sign, forcing my fingerprints onto my confession.

Before I was finally released, they asked me if I had a guarantor. I realized they were planning to release me on bail, a thought that hadn’t previously crossed my mind. I gave them my parents’ contact details. After some time, my parents and Chengdu State Security arrived to take me back. I was not allowed to return to Beijing.

Even after they released me from RSDL, I wasn’t completely free. Beijing State Security continued to harass me. They would come to Chengdu every few months, sometimes with one of my interrogators. Each time they came, I can’t describe how horrible I felt. I didn’t want to meet them, or think about them, but I had to do as they ordered. Chengdu police did as their superiors in State Security commanded. Generally, they weren’t too bad but for an entire year I was required to ask for their permission if I wanted to leave Chengdu for any reason. As a human rights lawyer who was used to taking cases around the country, this had the duel effect of cutting me off from my livelihood and closing another door of access to justice for victims who I might otherwise have defended or advised.

The chapter by Chen Zhixiu is titled Arise, ye who refused to be slaves and can be read in full, together with the other 11 stories in The People’s Republic of the Disappeared, available in paperback and e-book. The foreword is written by exiled lawyer Teng Biao. At the end of the book, Caster also analyzes RSDL from a legal perspective.

You might also like

More from Book Reviews

Lawyer, Advocate, Activist: Chiu Hsien-chih’s Vision for Justice in Taiwan

In his book ‘Stand By You,’ human rights lawyer Chiu Hsien-chih examines major human rights cases, problems with Taiwan’s legal …

New Book of Tibetan Short Stories Challenges China Narrative

‘Old Demons, New Deities’ will resonate in Taiwan, a country that, like Tibet, is torn between the competing realities of …