A direct U.S. military presence in Taiwan would do little to provide broader stability while increasing the risk that both China and Taiwan would assume the worst from a Trump strategy of unpredictability.

Former U.S. ambassador to the United Nations and Trump adviser John Bolton suggested recently that the U.S. should increase military sales to Taiwan and stated the possibility of once again stationing U.S. military personnel on the island-nation. One of the benefits of the latter, Bolton said, would be to ease tensions related to the U.S. presence on Okinawa.

On its face, such an explanation appears to overestimate the benefits of easing an admittedly longstanding point of contention with Japan and to underestimate the ramifications of heightening tensions with China during a Trump transition period already viewed as less predictable. Regardless, Bolton’s comments are consistent with justifying a broader American commitment to Taiwan, though bold suggestions about altering U.S. policy on Taiwan as a means to confront China require greater attention to the expected outcomes.

The U.S.’ formal military presence in Taiwan ceased in 1979 following president Carter’s switch of diplomatic recognition to China and unilateral termination of the Mutual Defense Treaty of 1954, although American arms sales have continued since under the Taiwan Relations Act (TRA). Despite Chinese complaints, U.S. sales will continue for the foreseeable future, but the size of and pace of deliveries are less certain. From a legal perspective, President Trump could initiate the return of an American military presence to Taiwan, although such a move appears to conflict with the spirit of the three U.S.-China communiqués.

Bolton, in line with statements from other Trump advisers, appears to see Taiwan’s role in U.S.-China relations instrumentally, a part of a “diplomatic tool of escalation” where the threat of increased diplomatic and military ties will restrain Chinese actions. For example, according to this view the “Taiwan card” provides means to challenge China’s assertions over control of the South China Sea, suggesting that China’s aggressive pursuit of maritime claims will push Taiwan to pursue closer relations with the U.S.

However, the Trump administration risks underestimating the danger of playing the “Taiwan card.” The 1995-1996 missile crisis after the Clinton administration approved a visa for then president Lee Teng-hui highlights how actions that would be minor diplomatic rows in other contexts can quickly escalate across the Taiwan Strait. China’s protests regarding an emergency landing of two U.S. F-18s in Taiwan in 2015 show how just the appearance greater U.S.-Taiwan military coordination can heighten tensions. Chinese opposition to a more transparent and deliberate measure to use Taiwan — such as serious discussion on upgrading diplomatic relations or a formal U.S. military presence in country — would be unlikely to blow over so quickly. Furthermore, China certainly has multiple means to frustrate American interests in the region as a response to perceptions of stronger engagement with Taiwan, most notably with regards to North Korea.

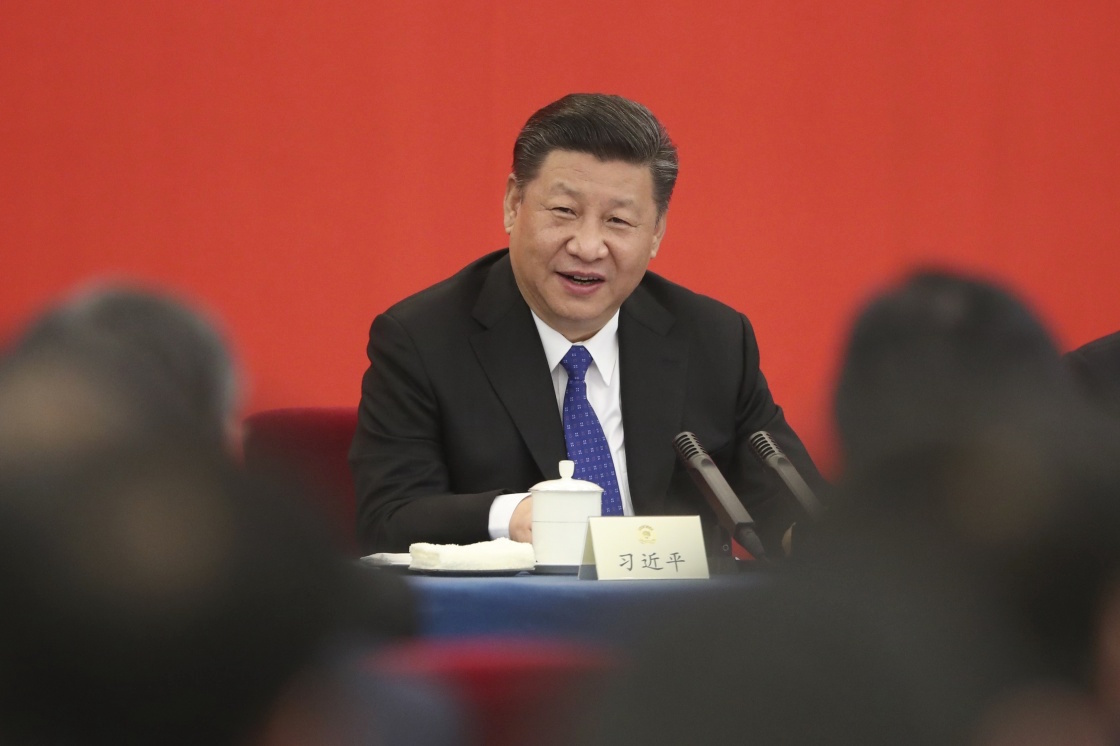

Former U.S. ambassador to the U.N. and Trump adviser John Bolton speaks at a conference in 2010. (Photo: John Bolton’s Facebook page)

The Trump camp rightly points out that U.S. relations with Taiwan should not be determined simply by China’s interests. However, upgrading U.S.-Taiwan ties should be predicated on Taiwan having already met the basic criteria of statehood and its growing economic and political importance in international relations, not as a bargaining chip that can be negotiated away if China makes whatever overtures the Trump administration desires. Chinese officials frequently reiterate that their country’s positions on Taiwan’s status and acceptable U.S.-Taiwan relations are non-negotiable, while an abrupt departure from this stance will have domestic costs in China. Perhaps most problematic, it is unclear whether the Trump administration would be prepared to cash in the “Taiwan card” under the highly improbable scenario that China did alter its behavior. As Alastair Ian Johnson points out, coercive diplomacy requires the coercer to reward desirable behavior. If the U.S. continued to signal an intent to deepen relations with Taiwan in this scenario, China would then have no reason to consider future American offers.

Furthermore, viewing Taiwan relations instrumentally underestimates the country’s own agency by assuming that the Tsai administration in Taiwan is willing to play the circumscribed role the Trump administration puts forward. For example floating the possibility of an American military presence in Taiwan may serve to put China on notice, but assumes that Taiwanese officials are ready to support this change. Similarly, Taiwan is unlikely to remain quiet if a Trump administration appears to sell out a longstanding partner. Ignoring Taiwan’s strategic interests here mirrors a similar pattern in the aftermath of “the call” where most attention focused on Trump’s acceptance of the call, rather than the dynamics that led Tsai to place the call.

Bolton’s comments suggest the Trump administration expects growing tension for the foreseeable future in East Asia. Several analysts have called for ways to reduce tensions, including a one-year détente between U.S. and China. While well-intentioned, this mirrors in many ways the proposal of Kenneth Lieberthal in 2005 to reduce cross-strait tensions by having both sides commit to delay a decision on Taiwan’s status for fifty years. Both proposals assume that the time off will bring the countries closer to an acceptable resolution on presently intractable disputes. Yet in the twelve years since Lieberthal’s proposal, changes in Taiwan have made unification less likely than ever while China not only remains just as committed to unification as before but possesses greater economic and military might to press the issue. A one-year détente as presently suggested would likely have a similar effect of moving the relevant parties further apart.

As China steps up efforts to isolate Taiwan diplomatically, improving U.S.-Taiwan relations gains greater importance. China’s military modernization requires Taiwan to respond and with other countries unlikely to increase military sales to Taiwan, the U.S. should find the means to fill this need. But suggesting the return of a direct U.S. military presence, however far-fetched in practice and even if suggested solely as a negotiating tactic, does little to provide broader stability and risks both China and Taiwan assuming the worst from a Trump strategy of unpredictability.

You might also like

More from Cross-Strait

Taiwanese Celebrities Who Bow to China: A Tempest in a Teapot

Taiwanese entertainers Ouyang Nana and Angela Chang have sparked controversy in Taiwan over news that they will perform at China’s …

In Memoriam: Lee Teng-Hui and the Democracy That He Built

The former president of Taiwan is the incontestable refutation of the belief that history is merely an impersonal force, that …

The Making of ‘Insidious Power: How China Undermines Global Democracy’

A new book released on July 30 takes a close look at the agencies and mechanisms of CCP 'sharp power' …