It is in the mutual interest of both Taiwan and China to reach an understanding by which they can conduct routine exchanges between their respective authorities, not least so as to avoid miscalculations.

After Ma Ying-jeou assumed office in 2008, the so called “1992 consensus” formed the basis of interactions between Taiwan and China. According to both the Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT) and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), this formula should form the basis of any and all contact between the two sides, without which the “ground will tremble and the mountains shake.”

President Tsai Ing-wen’s election and subsequent refusal to acquiesce to the aforementioned political framework has arguably moved Taiwan-China relations into a relatively new position. While it is true that president Chen Shui-bian (2000-2008) also refrained from accepting the “One China principle,” which the “1992 consensus” ostensibly is, global developments have transformed the environment on both sides of the Strait.

China is not only internationally more assertive than it was during the Chen administration but its military is unquestionably far more potent, as is its economic leverage.[1] It is debatable as to whether or not an alleged reduction in tourists or the courting of official diplomatic allies of questionable value amounts to a serious crisis or threat to Taiwan. Indeed, under these current circumstances Taiwan need do little to see the material continuation of the loosely defined “status quo.” However, signs of intensifying attempts to isolate Taiwan from countries that it enjoys unofficial relations with, while not an entirely new phenomenon, may cause a slight uneasiness among a Tsai administration seeking to maintain a reputation of reliability, responsibility, and competence.

It would thus appear that while Taiwan in the immediate future does not need to urgently reformulate its approach to relations with China, the new ruling party should begin to contemplate a potential new framework. The Tsai administration, and Tsai herself, has stated it is open to discussions at the highest level, provided there are no preconditions. The Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) has gradually come to appreciate that despite ideological differences it must cultivate some form of working relationship with China. To this end, President Tsai has demonstrated goodwill not merely with her words during her inaugural address but also in actions, such as refraining from immediately seeking re-admission to the UN and the consistent use of Ma era terminology in official contexts such as “Chinese Mainland” (中國大陸) and “Huá” (華) instead of “Tái” (台) in reference to Taiwan, all despite domestic pressures to do so.

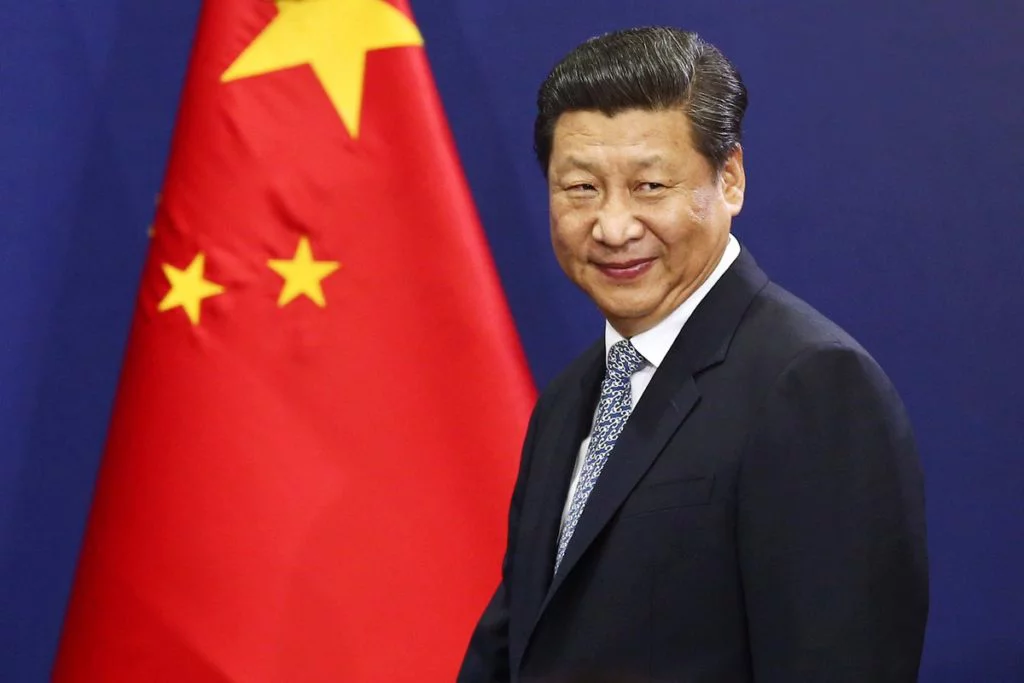

The drastically changing, or changed, identity landscape is well known, but perhaps more crucial are the shifts in party identification. The upward trend in individuals identifying with the DPP overtook the KMT in 2014 and currently stands almost 10 percentage points ahead. In addition, those identifying as pan-green have also overtaken the number of pan-blue individuals for the first time, again by almost 10 points. If these trends hold and are expressed by the DPP becoming the dominant party in the long term, both in the legislative and executive branches, it stands to reason that the CCP must establish some form of consistent and institutionalized relationship, especially if China seeks to maintain a modicum of influence within Taiwan. While President Xi Jinping has been quoted saying that political issues surrounding Taiwan cannot be left unresolved indefinitely, prolonged refusal to engage with the dominant political party in Taiwan is unlikely to bear the desired fruit and may in fact be highly counterproductive, reinforcing the Chinese government’s already abysmal image.

Taiwan’s Importance to the CCP

Since Tsai’s election the message emanating from Beijing indicates that it actually cares very little for the wording “1992 consensus,” with the recurring theme of the “One China Core” (一個中國核心) rising in prominence. For Beijing’s part, this to a certain extent expresses a degree of willingness to negotiate on semantics. China’s rigid insistence on “unifying” Taiwan, however, goes deeper than haughty rhetoric and represents a so-called “core interest.”

Historically speaking, and in traditional Chinese thought, “China” or the concept thereof has been “bounded by natural geographical features,” with the Taiwan Strait placing Taiwan outside of what could be considered China-proper.[2] Thus it might seem rather peculiar that in the latter half of the 20th century Taiwan has taken on such central importance; indeed, both Mao Zedong and Chiang Kai-Shek had voiced support for an independent Taiwan prior to the outbreak of World War II.[3] This indicates that Taiwan as a “core interest” has its true origins in political and strategic interests that rapidly incorporated ideological elements. Legitimate or not, these ideological elements nevertheless play a key component in Chinese policy-making and thus deserve serious examination by those seeking to engage with China.

Can President Xi withstand nationalistic pressures and find new common ground with Taiwan?

While Taiwan has undoubtedly been a point of contention for the CCP since the end of the Civil War with the KMT, the emphasis placed on Taiwan’s importance has certainly increased since the advent of the so called “Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation” (中華民族偉大復興). A persistent theme throughout this doctrine is the weight afforded to sovereignty and territorial integrity. This is not accidental: as has been observed, nationalism in China has increasingly been used as a substitute for Marxism as the state ideology.[4] Significantly, part of the narrative supporting this nationalism is China as a victim of imperialism. Where legitimacy once flowed from economic prosperity, it now also rests on the CCP’s ability to protect Chinese sovereignty — Taiwan essentially stands as the last major territory “lost” during the “Century of Humiliation,” without which the Party cannot claim to have fully restored China’s “intrinsic territory” (固有之疆域) nor its international prestige.

In line with the restoration of international prestige is the second element of China’s “rejuvenation,” which seeks to establish, or re-establish, China as a major global power. Somewhat paradoxically, however, is that China’s treatment of Taiwan, as well as its actions in other disputed regions, directly undermine and are contrary to achieving this goal. Chinese scholars have noted that military and economic might alone cannot secure recognition as a great power, and that cultural influence is essential.[5] The Chinese state has also acknowledged this, as is evident by the extensive expansion of its Confucius Institutes, as well as recent forays into the American, as well as other film industries.

It would therefore seem that China has two ambitions that increasingly are at odds with one another, and the CCP must in some way work to reconcile these two. Interestingly, despite the considerable weight afforded to both issues, they each have a central theme that stems from the CCP’s concern of legitimacy. It can thus be inferred that the fundamental “core interest” is the preservation of the current political system, or in other words the preservation of CCP supremacy. This is of course inherently fluid, and the regime can be expected to, and will, adjust itself to shifting expectations, for better or worse.

As a caveat, as exemplified in Deng Xiaoping’s famous strategy of “keeping a low profile” (韜光養晦,有所作為), in addition to China’s opaque decision-making system, interpreting ambition and in turn interests is at times anything but straightforward.

A Historic Community?

The impasse that exists between the DPP and China regarding the “1992 consensus” is multi-layered. It is true that many DPP politicians and members flatly reject the premise of “one China,” but for the current administration the issue appears to center on the issue on sovereignty. The DPP as a whole has long since compromised on the semantics of the Republic of China (ROC) as the title of the state; the problem lies in the subordinate position that the “1992 consensus” places Taiwan in relation to the People’s Republic of China (PRC), which Taiwan has never been a part of. Consequently, any wording that is used must be ambiguous enough to allow Beijing to continue to claim Taiwan as part of China while simultaneously allowing the DPP to assert that it does not subscribe to the “One China” framework.

The so called “1992 consensus” was workable due to its exploiting spatial ambiguity in its definition of “China.” The DPP could therefore creatively opt to attempt to expand this spatial ambiguity to also comprise a measure of temporal ambiguity. By employing language akin to saying that Taiwan and China are part of a “Historic Community” (歷史共同體) of some sort, the DPP could utilize the strong cultural and historical connections between Taiwan and China to bridge the ideological gap that exists between Taiwan and China while maintaining Taiwan’s claim of sovereignty. Such a formulation does not inherently imply a current political or sovereign connection, but is does not preclude it either.

the so called “1992 consensus” was workable due to its exploiting spatial ambiguity in its definition of “China.” The DPP could therefore creatively opt to attempt to expand this spatial ambiguity to also comprise a measure of temporal ambiguity.

On Beijing’s part, it may be prudent to start evaluating its relationship with its “frenemy” the KMT. What is now recognized as the Taiwanese Independence movement has its origins as a resistance predominately seeking justice from an oppressive ROC regime, a struggle that the CCP can arguably relate to. Recognizing, but not endorsing, the DPP and other independence groups as a result of poor KMT administration would go some way to rectifying the unreasonable radical characterization that has led Beijing to halt substantial interactions with Taiwan. Furthermore, it would to a certain degree unpeg itself from the spillover of negative sentiment that is associated with resistance to measures of transitional justice. This is undoubtedly unlikely, but there are signs that Beijing is beginning to realize that the KMT is an unreliable, and perhaps even counterproductive, proxy.

Going further, arguably the pursuit of a special, historic, and cultural relationship, à la the U.K. and the U.S., would serve China’s geostrategic interests and more effectively endear it to the Taiwanese people.

Feasibility

Chinese Opposition

The most significant stumbling block for the formation of any framework between the DPP and CCP is the rise of Chinese nationalism. This is a problem of China’s own making; in re-aligning its base of legitimacy it now finds itself in an effort to accommodate increasingly robust demands and expectations from society.[6] The effective characterization of the DPP as troublemaking separatists has meant that despite the government’s significant control over the state and media it has become increasingly constrained in the ways it can shape its foreign policy,[7] particularly with regards to Taiwan and even the South China Sea. The passing of the Anti-Secession Law (2005) could be viewed as such an example of responding to domestic nationalistic populism. Nationalistic sentiment with regard to so called “territorial integrity” has become so entrenched in contemporary Chinese rhetoric that scholars such as Zhao have stated that the prevention of the establishment of a Taiwanese state has become one of the indices by which the population measures the government’s performance.[8]

For China, the issue of Taiwan has in many ways moved beyond “mere” sovereignty; for the CCP it has entered the realm of at least being perceived as vital to the regime’s survival. Thus ambiguity, and implicitly compromise, may no longer be tolerable for a regime endeavoring to maintain the appearance of building a strong and influential China. Furthermore, formulation of policy itself seems to have reached a point where constructive creativity has been stifled. While to some extent this can be attributed to domestic pressure, the upcoming 19th Party Congress means that any policy change vis-à-vis Taiwan is unlikely to be seen or felt until the end of 2017 or early 2018.

Taiwanese Opposition

The Tsai government has demonstrated it is not seeking to have its administration defined through the lens of Taiwan-China relations, instead choosing to focus on major domestic issues such as pension reform and issues of transitional justice. Hence, while it has signalled a willingness to engage with China, it may not be looking to commit the extraordinary amount of time needed to promote and defend a new framework — nor may it have the political capital to do so.

In addition, the DPP still, at its core, supports the establishment of a Taiwanese state and for some voters any negotiation may be seen as an ideological betrayal. Nevertheless, although perceived compromise on sovereignty is a contentious issue, there has been increasing controversial debate on the viability of Taiwan embracing a “Finland model”; surprisingly some prominent DPP figures have spoken publicly of a scenario that sounds not too dissimilar, demonstrating that there is certainly flexibility to be found.

Speaking more broadly, however, one must consider the damage done by the so called “1992 consensus.” Despite claims to the contrary, this framework accomplished very little in terms of resolving or even addressing the underlying problem, which is significant as it was official government policy for eight years. Moreover, China engaged in highly visible activities that quite obviously violated the spirit of said “consensus,” calling into question the true value of any agreement reached with Beijing.

‘Win-Win’

It is in the mutual interest of both Taiwan and China to reach an understanding by which they can conduct routine exchanges between their respective authorities, not least so as to avoid miscalculations. For Beijing in particular, isolating Taiwan and its people is contrary to their desired outcome; isolation does not breed familiarity, nor is it endearing.

Vital to the creation of mutual trust and cooperation is the understanding of each party’s respective interests, even if one does not support them. The DPP must, if only internally, recognize that currently the CCP believes Taiwan is essential to its survival, not as an altruistic gesture of goodwill but in order to fully comprehend China’s resolve. Similarly, Beijing must come to terms with the reality that realistically there is little to no chance of any form of political integration in the near future. More importantly, China should refrain from portraying the Taiwan “issue” in a zero-sum manner to its domestic audience; the train of thought that states due to “pessimism” surrounding “peaceful unification” China will invade Taiwan is particularly worrisome [9] and even dangerous if coupled a growing domestic demand to deliver results.

Beijing must come to terms with the reality that realistically there is little to no chance of any form of political integration in the near future.

Somewhat ironically, given the troublesome experience China has had in governing other peripheral regions such as Hong Kong and Xinjiang, it is unlikely it relishes the thought of trying to administer a Taiwan “unified” through a bloody war. Interestingly, this line of thinking was best vocalized by Mao himself in a meeting with Henry Kissinger when he said that China would not want Taiwan at that point in time due to the presence of too many “counter-revolutionaries” and that it was “better to have Taiwan under the care of the United States [for] now.”[10] While the ideologies have certainly changed, the resistance to rule by the CCP has not, and Taiwanese society is ill-fitted for integration into the PRC as it currently exists.

Promisingly, there are precedents for rhetorical and strategic shifts, as demonstrated with the drop in salience of the “One Country, Two Systems” framework and the adoption of a strategy to prevent the de jure creation of a Taiwanese state,[11] which gives some hope for a future recalibration, in spite of Chinese indications to the contrary.

[1] Yuen, S. (2014) Under the Shadow of China. China Perspectives, 2014(2) 69-76.

[2] Teng, E. (2007) Taiwan in the Chinese Imagination, 17th – 19th Centuries. The Asia-Pacific Journal, 5(6) 1-31.

[3] Hsu, C. J. (2012) The Construction of National Identity in Taiwan’s Media, 1896-2012. Leiden, The Netherlands: Koninklijke Brill.

[4] Tang, W. and Darr, B. (2012) Chinese Nationalism and its Political and Social Origins. Journal of Contemporary China, 21(77) 811-826.

[5] Kallio, J. (2015) Dreaming of the Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation. Fudan Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 8: 521-532.

[6] Li, Y. (2014) Constructing Peace in the Taiwan Strait: A Constructivist Analysis of the Changing Dynamics of Identities and Nationalism. Journal of Contemporary China, 23(85) 119-142.

[7] Zhao, S. (2013) Foreign Policy Implications of Chinese Nationalism Revisited: The Strident Turn. Journal of Contemporary China, 22(82) 535-553.

[8] Zhao, S. (2006) China and Conflict Management: Conflict Prevention across the Taiwan Strait and the Making of China’s Anti-Secession Law. Asian Perspective, 30(1) 79-95.

[9] Kastner, S. L. (2015) Is the Taiwan Strait Still a Flash Point? Rethinking the Prospects for Armed Conflict between China and Taiwan. International Security, 40(3) 54-92.

[10] Chow, P. C. Y. (2008) The “One China” Dilemma. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

[11] Hickey, D. V. (2006) Foreign Policy Making in Taiwan: From Principle to Pragmatism. London: Routledge.

You might also like

More from Cross-Strait

Beijing Was Cooking the Frog in Hong Kong Well Before the National Security Law

Well before the coming into force of the NSL on July 1, the special administrative region had already become a …

President Tsai’s Second Term and Cross-Strait Relations: What to Watch Out For

The next four years will be marked by uncertainty over China’s trajectory and the state of the world in the …

As Coronavirus Crisis Intensifies, Beijing Continues to Play Politics Over Taiwan

With a major epidemic on its hands, the Chinese government has not ceased its political warfare activities against Taiwan. It …