While Taiwan endeavors to bring its legal system more in line with global liberal democratic standards, under Xi Jinping the rule of the CCP remains an absolute priority, and the law is being fashioned into an increasingly powerful instrument of party control.

On Oct. 10, President Tsai Ing-wen delivered her National Day address in which she raised transitional justice, a key area of Taiwan’s legal reform and an important step in completing the country’s transition away from its past authoritarianism to a full-fledged liberal democracy. Across the Taiwan Strait, China’s increasingly repressive measures toward any potential opposition, from the disappearance of famous actress Fan Bingbing to the reported internment of a million Uighurs, highlight the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) commitment to a hard authoritarian path for China’s future legal development under President Xi Jinping.

Both Taiwan and China are civil law countries with legal systems that have developed in tandem with dramatic political shifts from oppressive authoritarianism to liberalization. Moreover, since China’s change of administration in 2013 and Taiwan’s in 2016, both countries have taken measures to spur legal reform. However, the paths for legal development in Taiwan and China over recent years have proved to be markedly different, so much so that a sharp contrast between the strengthening rule of law in Taiwan and the hardening rule by law in China has become increasingly salient.

President Tsai’s highlighting Taiwan’s transitional justice in her National Day address this year is significant for two main reasons. Firstly, with the end of martial law having been declared as late as 1992 in areas like Kinmen and Matsu, transitional justice is integral to Taiwan’s process of coming to terms with its not-too-distant authoritarian past. Secondly, in the context of China’s increasing tendency to impose its authoritarian agenda at home and overseas, Taiwan’s emphasis on legal reform and democracy signals the country’s contrasting soft power approach on the international stage.

Reforms in transitional justice over the past two years demonstrate the Tsai administration is seeking to consolidate Taiwan’s role within in the region and the broader international sphere by making it a model for the development of democracy and rule of law.

Reforms in transitional justice over the past two years demonstrate the Tsai administration is seeking to consolidate Taiwan’s role within in the region and the broader international sphere by making it a model for the development of democracy and rule of law. For example, the Transitional Justice Commission, launched on May 31, 2018, was tasked with compiling an accurate report on Taiwan’s period of authoritarian rule, making political archives more accessible and redressing judicial injustices that occurred under martial law. In 2017, the administration annulled Article 9 (Paragraph 2) of the National Security Act of 1987, a measure that had prevented political victims convicted of criminal charges by court martial during the authoritarian period from appealing after martial law was lifted. Article 6 of the new legislation demands the right to appeal for re-investigation.

Besides transitional justice, the Tsai administration has also focused on other areas of legal reform, including last year’s proposed reforms to Taiwan’s judicial system. In February 2017, the fourth Preparatory Committee for the National Congress on Judicial Reform targeted protecting victims’ rights, promoting credibility, accountability and efficiency, transparency and public participation as well as maintaining social security as key areas for judicial reform. In July 2017, the sixth general meeting of the Preparatory Committee convened to focus more in-depth on civic participation in trials, with Committee Deputy Executive Secretary Lin Feng-jeng stating that the Judicial Yuan was drafting a trial system to introduce “citizen judges.”

In an address at the International Conference of the Constitutional Court earlier this month, Tsai discussed reforms underway at Taiwan’s Constitutional Court which would empower the body to review the constitutionality of rulings made by general courts and the Supreme Court. The proposed reforms, which are set to take force two years after the promulgation of the relevant bill, are based on the duties of Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court. Although these proposals have yet to be fully implemented, they reflect Taiwan’s commitment to bringing its legal system more in line with that of other modern, liberal democratic countries around the world.

In addition to these significant domestic reforms, Taiwan is also working to bring its legal system more in line with international standards. For example, Taiwan’s Ministry of Justice has been working closely with several legal experts and scholars from around the world since 2015 to amend the Law of Extradition. The Ministry of Justice has also completed a draft of the “International Mutual legal Assistance in Criminal Matters Law” as the legal basis of mutual legal assistance in criminal matters between Taiwan and the other nations. The retention of the death penalty, however, remains at variance with international trends.

In contrast with the promising developments in Taiwan, despite initial hopes for meaningful legal reform in China since the accession of Xi Jinping to power in 2013, including the creation of a Central Leading Group to advance law-based governance following the conclusion of the 19th Party Congress, China has unequivocally demonstrated it is committed to ruling by law. Under Xi, the rule of the CCP is absolute priority, while the law is being fashioned into an instrument of party control. This was exemplified in the passing of an amendment to China’s constitution to abolish presidential term limits back in March, a move which strengthened Xi Jinping’s grip on power by establishing a legal basis for his indefinite rule.

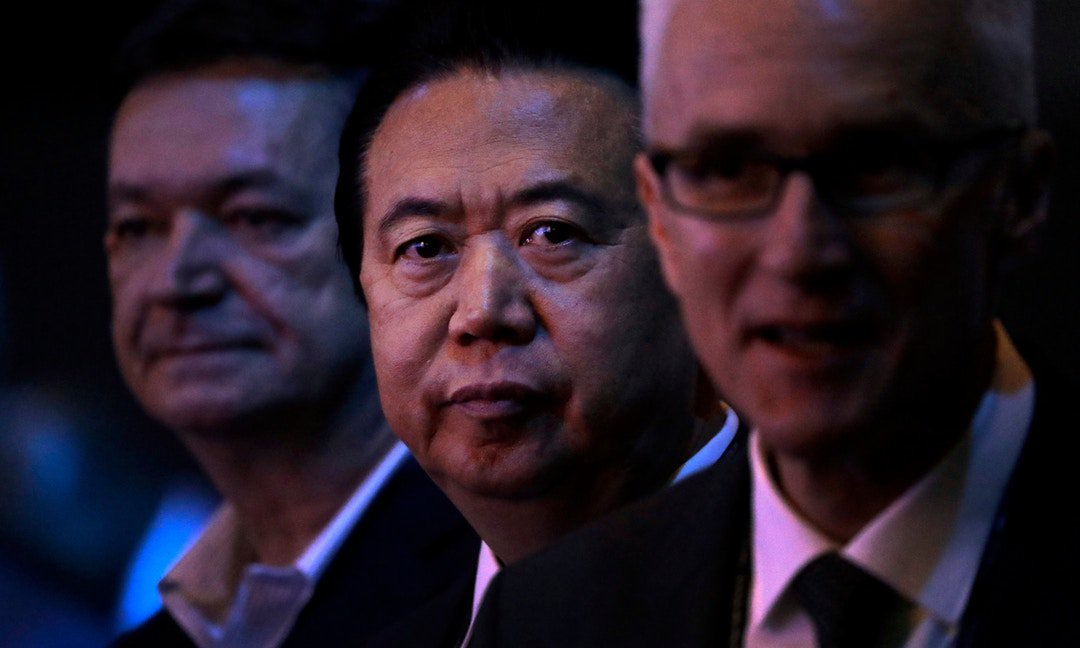

Similarly, reforms enacted to replace China’s shuanggui system with a system of “detention” (liuzhi) also reveal the driving force behind legal reform under Xi Jinping is tightening government control. Under the shuanggui system, party discipline inspectors had wide-ranging powers to interrogate party members suspected of corruption, including the power to secretly jail suspects. The new liuzhi system has proved to be little, if any, improvement from its predecessor, as most recently demonstrated with the detention of Interpol chief Meng Hongwei earlier this month.

Interpol chief Meng Hongwei, center, is the latest Chinese to have been disappeared into the legal system as President Xi Jinping hunts down every possible political opponent.

China’s strengthening rule by law is also increasingly evident in its hardline approach to Hong Kong. Although the “One Country, Two Systems” model is in theory meant to preserve Hong Kong’s separate legal system under the Basic Law, the National People’s Congress in Beijing has increasingly asserted its right to oversee the interpretation of the city’s laws in recent months. As a result, Hong Kong’s Basic Law has been interpreted in an increasingly restrictive fashion, with any perceived threat of opposition being deposed on the legal basis of protecting “national security.” For example, following the ban on the Hong Kong National Party in August, authorities cited a colonial-era law, Hong Kong’s Societies Ordinance, which supposedly empowered the government to ban groups “in the interests of national security, public order or the protection of the rights and freedoms of others.” Reputable foreign journalists, including Financial Times Asia news editor Victor Mallet, are now also being refused visa entry to the Special Administrative Region for the first time.

This trend of hardening rule by law within China reflects the Xi administration’s blatant disregard for the principle of rule of law, in which all institutions are subject and accountable to the law. The same values guiding China’s current legal development are also reflected in the country’s broader attitude toward international law, which it has oftentimes bypassed or sought to manipulate in its favor.

In light of growing concerns in the international community over China’s “sharp power,” its military aggression and use of economic clout to influence the international system, Taiwan’s reforms to strengthen the rule of law are marking the country out as an attractive, alternative model for legal and political development in Asia. As President Tsai declared in her National Day address, “the best way to defend Taiwan is to make it indispensable and irreplaceable to the world.” With each step taken on the path to better democracy and rule of law, Taiwan becomes closer to realizing this vision.

Top photo: President Tsai Ing-wen meets former South African president F. W. de Klerk, who played an instrumental, though not uncontroversial, role in ending Apartheid in his country, at the Presidential Office on Oct. 10, 2018 (photo courtesy of the Tsai Ing-wen official Facebook page).

You might also like

More from China

A Few Thoughts on the Meng-Spavor-Kovrig Exchange

It is hard not to see this weekend’s developments as a victory for China and the creation of a world …

As Coronavirus Crisis Intensifies, Beijing Continues to Play Politics Over Taiwan

With a major epidemic on its hands, the Chinese government has not ceased its political warfare activities against Taiwan. It …

Candidate Claims ‘Nobody Loves Taiwan More Than Xi Jinping’

Family business connections in the Pingtan free-trade zone and a son’s involvement with the CPPCC are raising questions about possible …